Having just returned from two weeks in the Orkney Islands working on the Ness of Brodgar excavation (see link to my blog entry and other dig diaries), https://www.nessofbrodgar.co.uk/dig-diary-friday-july-7-2017/, it is interesting to return to the Colne Valley and compare the two places. For someone living in 2017, July in Uxbridge could not be any more different from July in the northern archipelago of Orkney. The first major differences which tend to strike you are the climate and topography; on the first of this month I swapped the hot, humid, outer London cityscape for a flat, treeless, windswept landscape and weather which felt more like the beginning of spring than the midsummer I had left behind!

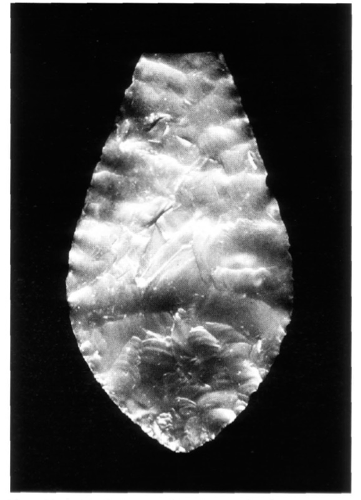

Rewind back to circa 3,500BC and the differences may have been a little less dramatic. Of the two places the changes in the physical geography are probably most strikingly observed in West London. Here, the commercial and residential developments, gravel extraction and transport infrastructures have obscured the river terraces, once seasonal wetlands associated with practices of animal husbandry and flint procurement. Woodland too would have been present along the valley, indicated in places not only by the types of pollen which have been recorded, but also by the surface scatters of leaf and laurel leaf arrowheads along the east bank of the Colne river, evidence of the hunting practices which continued well into the age of farming (Figure 1).

Even in this urban landscape, however, it is still possible to catch a glimpse of the Valley as it might have looked at the time of the early farmers and builders. At the Colne Valley Park visitors centre in Denham it is possible to experience a slice of the landscape as it might have looked during the Neolithic in a major prehistoric river valley (Figure 2).

In Orkney too it is possible to see landscape changes. The scenery near to current excavations at the Ness of Brodgar (Figure 3) is probably a little different from when the first stone foundations of buildings were laid. Recent pollen data as well as archaeological evidence of timber structures indicate that woodland was still scattered across the islands even into the Bronze Age. Although the Orcadian Neolithic were using stone for their buildings and monuments (Skara Brae, Barnhouse, Ness of Brodgar etc.) evidence for timber structures have also been found at Braes of Ha’Breck in Wyre. Pollen records also show diverse woodland of birch, hazel, rowan, willow, oak and pine which would have provided valuable resources in much the same way as woodland in the Colne Valley.

While it might now be difficult to envisage well utilised woodland in either landscape, during the Early Neolithic patches of forest would have been a lot more visible as well as entangled into the activities of daily life. These places would have sustained a variety of wildlife as well as provided valuable timber and vegetation, and would have influenced the routines of social inhabitation alongside emerging practices of cattle rearing, cultivation and construction.