While the vast majority of people have heard of the Green Belt, few know much beyond the fact it rings London and our other largest cities. Here, we take a closer look at the Green Belt and try to explain more about the crucially important role it plays in maintaining a balance between the environment in which we live, and the containment and management of urban development.

VIEWED from the midst of the politically turbulent waters of the 21st century, the idea of establishing the Green Belt seems miraculous.

For a start, it was an unusually innovative, far-sighted and extremely sound idea that has benefited generations of people and preserved vital green spaces which would otherwise have been engulfed by rapid and completely unco-ordinated urban development.

But despite the brilliance of that vision, the policy wording supposed to underpin it misses the point, focusing instead on what we don’t want, rather than what we do.

For example, we don’t want urban sprawl, but we do need to be able to manage essential development, appropriately mitigating its impact, and devoting thought and resources to creating and maintain a living environment that preserves what is irreplaceable and precious, while allowing the economy to breathe.

The Colne Valley Regional Park’s six objectives are aimed at addressing these issues, focusing on some of the missing positive aspects.

The role of the Green Belt is set out in paragraph 142 of the National Planning Policy Framework:

“The Government attaches great importance to Green Belts. The fundamental aim of Green Belt policy is to prevent urban sprawl… the essential characteristics of Green Belts are their openness and their permanence.”

And there’s one of the problems right there. It is worth pointing out that Green Belt is not a landscape quality designation – there is no reference to land being attractive, rich in wildlife, useful for food production, countryside readily accessible to people for recreation, nature study etc. All we have is reference to Green Belt simply being open and permanent.

We believe that Colne Valley Regional Park is the perfect case study for highlighting the flaws in the current understanding and treatment of Green Belt and the opportunities it can deliver to the benefit of the public. The Park sits in Green Belt on the western edge of London and at the boundaries of five counties. There is no joined-up thinking or co-ordination of planning in such a uniquely pressured area, and if nothing is done, it is no exaggeration to say the Park’s very existence could be threatened within a few years. You can read more about our campaign on this subject here.

A bit of history

Actually, Green Belt is not a new concept – you can even find the idea mentioned in the Old Testament of the Bible. The book of Numbers states:

The cities shall be theirs for dwelling, and their open space shall be for their animals, for their possessions and for all the amenities of life”.

The potential problems posed by unlimited expansion of towns and cities were also recognised by the Elizabethans, when a law was passed that stated: “No new buildings shall be erected within three miles of London or Westminster…”

The advent of the railways and cars within a comparatively narrow period of time brought with them opportunities to expand cities well beyond walking distance. Development of the countryside was swift driven more by commercial concerns than longer-term environmental impact.

It led to much debate in the early 20th century amid mounting concern about the lack of coherent planning for meeting the competing needs of housing provision , businesses and space for farming and countryside recreation.

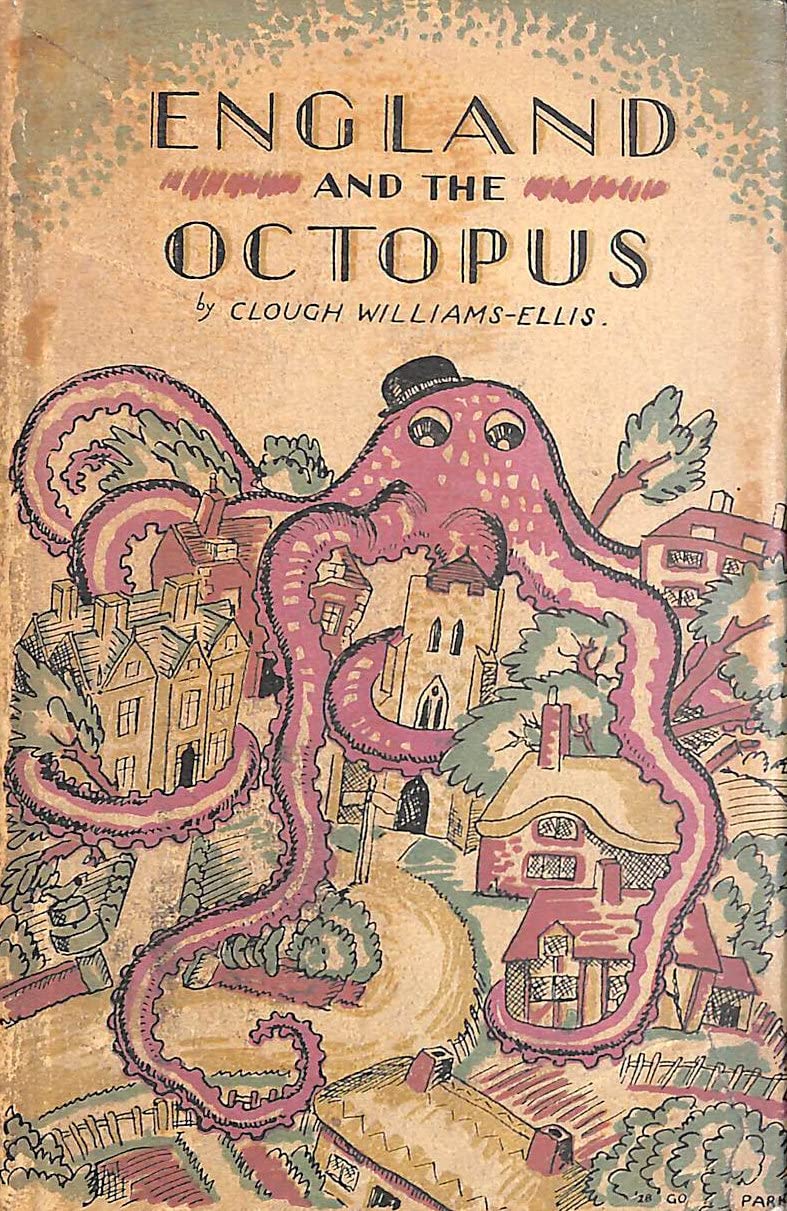

Sir Clough Williams-Ellis, the eccentric architect and creator of Portmeirion in North Wales, and pioneer of British National Parks and garden cities, wrote a polemical warning about the dangers posed by unlimited expansion of London in 1929. His book, England and the Octopus illustrated how the capital’s tentacles were spreading along major roads and swallowing up the countryside in a completely unplanned way.

He was well ahead of his time and his ideas contributed to the creation of the Green Belt. It worked for around 80 years, but now we have begun to slip back towards the unplanned development frenzy that prevailed in the 1920s. Today, it is the lack of strategic national planning and leaving the market to decide what strategic developments go where, that has become a pressing and potentially devastating problem 100 years after Williams-Ellis wrote his book.

Steps in the right direction

The 1938 Green Belt (London and Home Counties) Act was the first to address this problem, enabling councils to buy land to keep as open space. In these early days, councils were seen as safe pairs of hands, and large areas were purchased at reduced rates by forward-thinking authorities in our area.

In the wake of the Second World War it was no longer seen as feasible for local authorities to purchase all of the land required to maintain a functioning Green Belt. As a means of controlling development without interfering with ownership and land use, some planning authorities around London began writing restricted development policies into their Local Plans in order to stop the uncontrolled spread of London.

The Government approved of this idea, and in 1955 it issued a circular to all local planning authorities asking them to establish Green Belt in their Development Plans.

It’s thanks to those visionaries of the early to mid-20th century that the Green Belt has worked so effectively for nearly 80 years. In 1988, the Principles of the Green Belt were incorporated in Planning Policy Guidance, the forerunner of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

The creation of the Colne Valley Regional Park by local authorities in 1965 is an extraordinary example of strategic thinking and should be applauded. Since then the Regional Park has helped local authorities to implement NPPF para 150, focusing on the positive things that the countryside around London can do – giving people easy access to it, boosting health and well-being, promoting food production, providing space for nature and nature-based solutions, and adaptation to climate change.

The Park’s achievements since the mid-1960s include creation of five country parks, more than 50km of new paths and, more recently, delivering a £2.5m Landscape Partnership devoted to improving the area, its wildlife and paths, and helping people to discover the countryside on their doorstep.

The Green Belt has been one of the most enduringly successful and popular elements of government policy. It has maintained a clear distinction between town and country lacking in many other parts of the world.

Viewing the sprawl around places like Los Angeles or the viewpoint from Assisi in Italy show only too well what would have happened to the Colne Valley and other areas like it without the vision of our predecessors.

Steps in the wrong direction

The NPPF protects the Green Belt against development – unless a developer can prove that there are ‘Very Special Circumstances’.

In the Colne Valley (and many other places) this case is being made so frequently in recent years that it has become routine, something that is neither genuinely exceptional or in the spirit of the original policy.

Paragraph 150 of the current NPPF states:

“Local authorities should plan positively to enhance their [Green Belt’s] beneficial use, such as looking for opportunities to provide… outdoor sport and recreation; to retain and enhance landscapes, visual amenity and biodiversity; or to improve damaged and derelict land.”

This would be fine if it wasn’t for use of the word ‘should’. ‘Must’ would have been far better.

In the 2020s all is not well. The Green Belt faces its greatest threats. It is increasingly portrayed by developers, free-marketeers and lobbyists as simply a barrier to profit.

Since the abolition of regional planning in 2010, and the government’s failure to replace this with any kind of national plan, we have witnessed an enormous number of unco-ordinated development proposals bypassing previous obligations for the improvement of the remaining countryside around them.

The financial pressures on local authorities, the Environment Agency and Natural England, means that they are not always able to take swift and effective enforcement action against blatant planning breaches, leaving offenders free to continue operating illegally on Green Belt land, polluting rivers or destroying protected spaces for nature.

Finally, whilst much of the land acquired under the 1938 Act, such as Black Park, is still looked after, in the 2020s a worrying new trend has emerged. Funding for local councils was progressively reduced, driving some of them to seek increasingly drastic ways to find revenue from elsewhere in order to meet their statutory responsibilities. Unfortunately, the reasons for the acquisition of land for the long term public good all those years ago have been increasingly forgotten in favour of selling it off for short term income generation.

There are no shades of grey

The Green Belt is the Green Belt. There are – quite rightly – no sub-categories. Despite this, think tanks and others are advocating the release of large areas from the Green Belt to meet a growing need for housing or business use.

You may well have heard increasing use of the hugely misleading term ‘grey belt’. This has been conveniently coined by those seeking to erode the proven and long-standing Green Belt policy. It will lead to ‘planning by dereliction’. This is where landowners are encouraged to throttle positive use and deliberately allow landscape quality to decline. It is then so much easier to say: “That site’s an eyesore – it’s not even green – it should be developed.”

This Trojan Horse for swallowing previously valuable Green Belt land must be resisted (or adapted to recognise the potential of areas like the Colne Valley for people and wildlife), or our remaining green spaces are destined to be systematically eaten away.

So where do we go from here?

There is a genuine and urgent need for carefully co-ordinated management and creation of green spaces in areas like the Colne Valley Regional Park. This ‘green infrastructure’ includes properly joined-up thinking about parks, open spaces, playing fields, woodlands, trees in streets, allotments, private gardens, green roofs and walls and sustainable soil and drainage systems.

There is a genuine and urgent need for houses, data centres and some other large types of development.

What’s currently missing from the planning system is some form of national plan to balance those competing needs and create spatial plans for how and where that can be met.

If development is approved, then it must deliver local benefit, through better design and improved environmental mitigation to directly address the impact on people’s access to the countryside and to nature. Biodiversity net gain is not enough.

Any financial mitigation must be in proportion to the scale and impact of the development project. All too often, mitigation sums associated with multi-million pound projects are paltry and ineffective.

Our campaign makes the case for areas like the Colne Valley to be planned for, protected and enhanced to provide accessible high quality countryside for the benefit of people and wildlife.

Opportunities to improve the Green Belt must be taken by national government and your local council. Their predecessors had the vision and foresight to create the Green Belt and the Colne Valley Regional Park in the mid-20th century. There is no reason why this vision cannot be reclaimed in the 21st.